"Good Just Barely Morning ... "

How WNEW in New York Remade Radio and Became The Place Where Rock Lived: Chapter 14

Chapter 14

"Boy, I'm gonna tell you ... I'm going to teach you radio ... You are a star!"

— The words of Scott Muni’s first boss in radio, a “big, fat, balding, cigar-smoking” station owner the disc jockey would never forget.

Arde Bulova filed the papers finalizing the sale of WNEW on December 8, 1949. Two days later, a skinny teenager home on leave from the Marine Corps showed up at the back door of a century-old building at the corner of North Rampart and Dumaine streets in New Orleans, and fatefully stepped inside.

During the war, the business out front had been an appliance store with the lucrative sideline of servicing jukeboxes around the city. Among those who worked at the store was Cosimo Matassa, who noticed a steady flow of customers materialized whenever word spread of a new supply of used jukebox records on the premises.

In one of those instances where a moment of inspiration had long-term and unforeseen repercussions, Matassa bought the business, and immediately dropped the appliances. In their place, the young but practical-minded businessman installed additional record bins.

Then, knowing the Treme neighborhood directly across the street was bristling with young musicians, he took the additional step of converting the former storage room in the back into a recording studio.

Not that Matassa harbored dreams of being a great impresario; he simply realized there was additional money to be made in giving people an inexpensive way to make records for their own personal use. But that's where unintended consequences came into play.

Despite its being a spawning ground of some of the greatest jazz musicians of the early 20th Century, the Big Easy never gave rise to a significant recording industry. Soon, the newly minted J&M Music Shop on the edge of the French Quarter was teeming with acts with commercial aspirations.

Over the next decade, those who made their way to the studio's entranceway out back, behind the store, included Roy Brown, Lloyd Price, Big Joe Turner, Ernie K-Doe, Guitar Slim, Smiley Lewis and later, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis.

It was into just such a milieu that Donald Allen Muñoz walked on December 10, 1949. Muñoz, whom generations of New York radio listeners would come to know as “Scott Muni” was no musician, and certainly no singer, his preternaturally deep voice already possessing a bottom that sounded like two large slabs of concrete rubbing against one another.

Like many young people growing up in New Orleans at the time, he'd become enamored with the rhythm and blues emanating from the tiny studio. What set him apart from the rest, perhaps, was his determination to see what was going on for himself.

“I guess I was 18, 19 years old at the time,” Muni recalled in 1986 as he inducted the disc jockey Alan Freed into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. “Cosimo had Fats Domino in the studio. Lee Allen was on saxophone. And I got to hear Fats Domino record some hits.”

As the young man watched, Dave Bartholomew, Domino’s producer, spoke with the backing musicians, explaining how the song he and Domino had written should go. Since none of the musicians read music, Bartholomew hummed their respective parts.

Because of the primitive technology available to a studio operating on little more than a shoe-string budget, the band rehearsed the number again and again, until they could pull off what Bartholomew was looking for in a “live” take. As they rehearsed, a bottle was passed around to keep the band loose.

Then Domino sat down at the piano.

Muni, who never witnessed a recording session before, was amazed by the process. The experience cemented an enduring love for what was then an entirely new sound.

“I said to myself, ‘I really like this music,’” he remembered.

Years later, Muni loved to tell younger colleagues that he'd been a witness to history.1 For the rest of his life “Fats” was a nickname — an honorarium, really — that he would bestow on anyone for whom he really felt affection or a kinship.

Over the years, there would be varying descriptions of exactly what Fats Domino hit he heard recorded that day.

Legend among some of the younger staff members who later worked at WNEW-FM had it that it was “Ain’t That a Shame,” a huge national hit, the biggest of a string of classics Domino recorded throughout the 1950s.

The problem with this version of the story is that it can’t possibly be true. “Ain’t That a Shame” was the first of Domino's big hits not to be recorded in New Orleans. In fact, the song was recorded in a Hollywood studio on March 15, 1955 while Domino was on tour and appearing at Los Angeles’ popular Five-Four Ballroom.2

Muni himself provided the clue to unravel the mystery during the Hall of Fame remarks. If, as he recalled, he was no more than 19 at the time, the session he happened into had to have been Domino’s only recording date of 1949. Given the other details he provided, it’s certain what Muni witnessed that afternoon was the recording of Fats Domino’s first national hit, “The Fat Man.”

Just as certain is that the session was one of the defining moments of the young man’s life.

Born in Wichita, Kansas on May 10, 1930, Muni grew up idolizing his father, Francis Miguel (“Frank”) Muñoz, an aviator in the first World War, who in many ways represented the culmination of an immigration story with roots in post-Civil War era America.

The first significant record of the family's presence in the United States is the 1870 census. It reported that on June 1, 1870, a 51-year-old Venezuelan émigré named Manuel Muñoz — Scott Muni's great-great grandfather — was living in Brooklyn, New York with his 40-year-old wife and their eight children, aged 8 to 25.

Muñoz was identified as a produce broker, and the two eldest of his children were working as clerks in the family business. The family patriarch declared the total value of his personal property to be $2,700.

The second youngest child living in the household was 10-year-old James, who we next encountered on the 1900 census. By this time, James was a 40-year-old railroad worker, and he and his family had settled in Jacksonville, Florida.

The youngest of James’s two boys was Muni’s father, Frank, and it’s from him that one first gets the sense of quickly changing fortunes, both for the family and the country.

By January 1920, 24-year-old Frank Muñoz was out on his own, and lodging in St. Paul, Minnesota with a salesman of leather products and the salesman's music teacher wife.3

In the intervening decades Muñoz had attended high school in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, served in the World War, and graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Ga.

But like many former Army pilots, Muñoz found himself at loose ends after the war, wondering what to do with a hard-earned skill that had served him well in wartime, but which still had few civilian applications.

Some in his position began delivering mail, while others joined the daredevil circuit, performing death-defying stunts high above the attendees of state fairs and the like. While Muni's father may have dabbled in a little of both, when questioned, he gave his occupation as engineer.

Many decades later, his son would still recount with pride the role the elder Muñoz played in the development of a network of airports across the country, the impetus for which wasn't passenger travel, but the lucrative air mail route contracts being given out by the United States Postal Service.

Zach Martin, Muni’s producer during the final years of the radio legend's career, recalled a trip he took with Muni to the disc jockey's beach house in Toms River, New Jersey.

Muni, then 74, wanted to retrieve some things from the attic, and when he came back down, somewhat out of breath, among things he brought with him were pictures of his father, some of them showing a handsome young man in uniform standing in front of a biplane.

“Scott's looking at the pictures, and he gets a little teary eyed,” Martin said. “I asked him if his dad was a World War I pilot, and he said, ‘Well, let me tell you ... after the war, when they were trying to get airports built ... my old man would fly around the country in his biplane and he would land in certain fields in certain communities.’

“‘Now, some of the people who owned these fields would drive him out with shotguns, but others would be happy to talk with him,” Muni continued. Martin soaked in the tale.

Whether a coincidence or not, the record shows that the first hangar built at what is now the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport was a wooden structure erected in 1920 to accommodate airmail service.

The 160-acre site had been the location of an unsuccessful auto-racing venue, Snelling Speedway, which was purchased by the Minneapolis Aero Club in 1914. By 1923, about the time Muñoz was preparing to move on, the airport had been renamed Wold-Chamberlain Field to honor two local pilots who had been killed in the war.

Muñoz next stop was Atlanta, where, Muni told Martin, “he was able to talk to the mayor, who later championed the development of what would become [Hartsfield-Jackson] Atlanta International Airport.”

While anecdotal evidence is all one has to go on, the timing and many of the known facts of the Atlanta airport's development jibe with Muni's remembrance.

In late 1924, Atlanta Mayor Walter A. Sims proposed the city build a new airport and appointed a newly elected alderman, William B. Hartsfield, to find a location. As was the case in St. Paul, the 287-acre site eventually chosen for the airport was an abandoned auto racetrack. This time, it was one owned by the Candler family, which included Coca-Cola magnate Asa Candler.

Although auto racing had only started at the track in 1909, by the early 1920s, it had largely fallen into disuse and pilots passing through the area had taken to landing on its infield.

Mayor Sims signed a five-year lease on the land in April 1925, and after decades of development, the airport would become the world's busiest air hub in 2011.4

Even if he was destined to remain an unseen hand in the history of several American cities, Frank Muñoz was clearly a man on a roll in the 1920s. By the time he left St. Paul, he had married Olive Benepe, the daughter of Dr. Louis M. and Letia Benepe, and fathered a daughter, Emma.

The transient nature of his existence during this period is made clear from the 1930 U.S. Census, which found the young family living in Wichita, Kansas, and enlarged by the birth of two children, a son, John, and infant daughter Harriet. Significantly, despite the proximity of their ages (Emma was 7, John 6 and Harriet, nearly 2), none of the children were born in the same state.

However, this was about to change. Even as the Census taker was taking down their family information, it couldn’t have escaped his attention that Olive Benepe was very pregnant with another child.

In fact, the future Scott Muni was born just 21 days later. But the arrival of Donald Allen Muñoz, the second of the couple's children to be born in Kansas, wasn’t the only transition the family was going through.

Frank Muñoz lists something entirely new and wholly unexpected as his occupation during this, the second year of the great depression — traveling salesman for a "retail music house." The job, and the move to Wichita appear to have ushered in an extended period of stability for the family.

Ten years later, the Muñoz family still lived in the same home as they did in 1930, and its patriarch was still employed as a salesman.

With the onset of World War II, however, Muñoz’ engineering and aeronautical acumen were once again in demand. Not long after the United States entered the war, Muñoz was offered a position with the aviation division of Higgins Industries, a New Orleans-based manufacturer that was quickly positioning itself as a prime military contractor.

The division was established in 1942 with the objective of manufacturing transport aircraft for the U.S. Army Air Force.

As the war progressed, Muñoz was promoted to director of quality for Higgins Industries, helping to oversee production of the landing craft — informally known as “Higgins boats” — that were widely credited with making the D-Day landings at Normandy, as well as storming of the beaches at Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and Guam, possible.

General Dwight Eisenhower said after the war, “Andrew Higgins ... is the man who won the war for us. ... If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs5, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different."6

Higgins himself was a Nebraska native who went into the lumber business and eventually wound up working for a German-owned lumber-importing firm in New Orleans. He formed his own lumber exporting firm in 1922, and slowly expanded his business to include ownership of the vessels that moved his product and eventually, a shipyard and smaller boats to service them.

Higgins designed his first boat, a shallow-draft craft called the Eureka, in 1926, for use by oil men and trappers along the shallow Gulf coast and the marshes and bayous of the lower Mississippi Delta.

After the depression wiped out his exporting business, Higgins concentrated on boat building, eventually even winning the U.S. Coast Guard as a client. That connection eventually brought him attention from the U.S. Marine Corps., which was looking for a better way to transport its men for amphibious landing in battle conditions.

The service tried out the Eureka, liked it, but ultimately decided it had one fatal flaw — men and equipment had to disembark over the sides, making them vulnerable to enemy gunfire. During his discussions with the Marines in Washington, D.C., however, Higgins was shown a photograph of a Japanese landing craft that had a ramp as its bow.

Inspired, Higgins called the plant in New Orleans and told his chief engineer to develop a mock-up of such a craft. Within a month, the company was testing what was initially simply a ramp-bowed Eureka in Lake Pontchartrain.

Impressed, both the Marines and U.S. Navy began ordering large quantities of Higgins boats. By the time the war was over, the company would produce more than 20,000 of them along with PT boats, supply vessels and other specialized craft.

Muñoz was an integral part of the management overseeing the activities on a crowded production floor over which hung a banner that read, “The Guy Who Relaxes is Helping the Axis!”

It's impossible to know the culture shock and adjustment Muñoz’ youngest son experienced after the move from the Kansas plains to the Big Easy. Throughout his broadcasting career, Muni always expressed great pride in his New Orleans background.

At the time, New Orleans was America's busiest port, and the war, coupled with the region's shipping-centric infrastructure resulted in fairly good times for the city's working class.

The Muñoz family settled into an elevated single-family home at 7700 Nelson Street, in the Fontainebleau-Marleyville section of New Orleans.

Sixty years later, the area remains a modest, but solid neighborhood of tree-lined streets, small, unfenced yards and homes for which the front porch literally serves as an extension of the living room. Although not as opulent as some, the 4,200 square foot lot the Muñozes occupied did include the amenity of a detached garage.

What little is known of Muni's childhood falls into the category of the fairly typical: He went to school, hung out with friends, and earned a little bit of money delivering the Times-Picayune newspaper.

Zach Martin said Muni vividly remembered one incident related to his paper route.

One afternoon, a local priest who happened to be skirting his vows of abstinence with a young woman in the neighborhood backed over Muni's bicycle with his car.

Muni’s father confronted the priest, who was initially reluctant to make amends for the accident.

“He quoted his dad as saying, ‘Well, you're going to get my son a new bike, because he needs it to deliver his newspapers, and if you don't do it, I'll let everybody know what's going on here,” Martin said.

Muni was back in the newspaper delivery business the next day.

Although the disc jockey often shared such stories with colleagues over the course of his long career, surprisingly few such anecdotes crop up in the interviews he gave to publications over the years.

In his longest published reminiscence, a 1987 profile that appeared in Variety magazine on the occasion of WNEW-FM's 20th anniversary as a progressive rock station, Muni revealed the somewhat surprising fact that he grew up in a Crescent City home that was largely devoid of music.

“No one played piano or even records,” he told reporter Ken Terry.7

Muni, however, couldn't get enough of it. With friends, he soaked up the sounds of New Orleans' rich and legendary local music scene at every opportunity, helping himself to generous samples of traditional jazz, rhythm and blues, country and even Cajun music.

If the force of his father's personality and the rich musical gumbo of the city were two formative influences on Muni's later life, the sudden death of his mother just three years after the family moved to New Orleans was the shadow that would always linger just below the surface.

“I kind of got lost,” he said of the period.8

He rarely shared more about his mother's passing or its effect on his inner life.

A brief obituary published in the Times-Picayune on Sunday, June 3, 1945, said simply that Olive Benepe Muñoz died in her home at about 1:45 a.m. the previous day, and that a service was to be said for her that Sunday afternoon at the Christ Church Cathedral on St. Charles Avenue at Sixth Street.

Afterwards her remains were taken back to her hometown of St. Paul, Minn. for interment. She was just 48 years old. No cause of death was given.

Martin, who was especially close to Muni during the disc jockey's later years, said he only learned of Olive Muñoz's early death after his own mother was murdered by the serial killer Charles Edmund Cullen in 2003.

Cullen, who killed at least 40 patients during the 16 years he worked at 10 different hospitals in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, is considered the most prolific serial killer in New Jersey history and is suspected to be the most prolific serial killer in U.S. history.

Grief-stricken, Martin called Muni to tell him what had happened.

“He said, ‘I know how you feel ... mine died when I was 14,’” Martin said. “He didn't elaborate, but I could feel his empathy, and at the same time, I felt like he was saying you have to be strong and carry on. I think it was his way of pulling me out of my grief with a jolt of stark reality. It was very ... fatherly, in a way; perhaps at that point, grandfatherly.”

Muni’s response to his mother’s death in its immediate aftermath was to make what turned out to be an abortive attempt to join the Marine Corps.

According to Martin, Muni successfully got in, but was soon found to be under age and was sent home with the invitation to rejoin when he was old enough to enlist.

Settling back into a routine, Muni attended both the Alcee Fortier and S. J. Peters high schools, on Freret and South Broad streets, simultaneously, a not uncommon occurrence in a school system where resources were thin and attendance numbers fluctuated significantly.

And it was at the latter school, during his junior year, that another significant turning point occurred in Muni's life. He would later tell Pete Fornatale9 that everything that followed began with a friend who happened to own a car.

“Anybody who had wheels in high school was a big deal,” Muni said.

The problem was that Muni had the last period off while his friend had speech class at the end of the day.

"So I used to wait for him, sitting in the back of the class, and after several days of this, the teacher turned to me and said, ‘I don't mind you staying here, but if you're going to stay, I want you to participate.’

Muni resisted for what he said were three or four of these encounters, before finally relenting.

He wouldn't get credit for the class, but he memorized all the assignments after that and presented a few of them in front of the class.

Muni would always claim the teacher took to him because he spoke “fairly straight,” Midwestern English when all the other students spoke in the drawls of the Deep South. Along with that, he might have added, he’d also begun to develop his unusually deep, resonant voice.

“I kind of stuck out like a sore thumb,” he told Fornatale.

Sensing he'd discovered a diamond in the rough, the teacher encouraged Muni to sign up for the advanced speech class the following year. When Muni agreed — and continued to excel — the teacher encouraged his star pupil to enter something called the Hi-Lites announcer's contest, a 1947 competition for which the first prize was a daily, 15 minute school news broadcast on a local radio station.

Muni won. And the experience culminated with his being chosen to be the moderator for the big year-end, all-school broadcast.

“When I got home that night, it must have been around 5 o'clock, there was a message for me to call this local radio station,” Muni said.

The caller was the manager of the station who had heard the teenaged announcer and immediately offered him a job.

“I'm never going to forget that man,” Muni said 40 years later. “This guy was ... big, fat, balding, cigar-smoking.”

In making his pitch to the young man, the station boss said, “Boy, I'm gonna tell you ... I'm going to teach you radio ... You are a star!”10

Muni soon found himself behind the microphone of what he'd describe as “a little, hole-in-the-wall station” deep in bayou country, playing short segments of music, and then spending long stretches reading the news, local commercials and birthday and anniversary announcements, barely being able to pronounce the creole and Cajun names that filled his copy.

“It was very, very strange and definitely a baptism by fire,” he said. “At the same time, I was working with men who were twice my age, which could be a challenge in itself.”

Although he reliably showed up every day after school to work his 6 to 8 p.m. shift; the teenager soon discovered his new boss only had a loose grasp of the concept of paying his protégé for his time on the air. In fact, the station, such as it was, was experiencing serious financial problems, its staff not having been paid for several weeks.

“Scott said the staff finally got so fed up they decided to do a wild cat strike, and as part of this, they wanted to take the station off the air,” Martin said. “The problem was, all of these people had families, and they knew whoever turned the transmitter off was most likely going to be fired.”

Being too young to have a family of his own, Muni volunteered and threw the switch.

“So right there, you understand some of the things he learned from his Dad,” Martin said. “This work ethic and the idea of integrity and the difference between right and wrong, along with being a man and standing up for and advocating for the little guy. That was his personality at that point and he would always remain that way.”

That Muni did get fired — he never explicitly told Martin whether he did or didn't — appears evident from statements he made to others that the strike was “the last radio for me for quite some time.”

Within days of his 18th birthday, Muni returned to the recruiting office and this time, the Marine Corps welcomed him.

He reported to the Marine Corps Recruit Training Depot at Parris Island, S.C. on July 1, 1948, and by the time he left, 30 days later, he was not only a full-fledged member of the service, but was also headed back into radio.

Muni’s radio experience and distinctive voice initially carried him west, to the Treasure Island Naval Station in San Francisco Bay, and then to the Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base in San Diego.

His “break,” however, came in July 1949, when the private first class was told he'd been temporarily attached to Guam and Armed Services Radio Station WVTG. Initially, he was the station's jack of all trades, filling any shift and taking on minor tasks the station's more established and higher ranking hosts considered beneath them.

But Muni couldn't have been happier. It was on the remote Pacific island that he first began to think he could have a viable career behind a microphone. Therefore, he reasoned, most every assignment that came his way -- no matter how unglamorous — was a crash course in something he'd need to know later.

The “studio” Muni inhabited during his nine months in Guam was a cobbled together collection of worn tables and chairs bearing all the marks of just-get-it-there, rather than handle-with-care — a telltale sign of frequent and abrupt relocation.

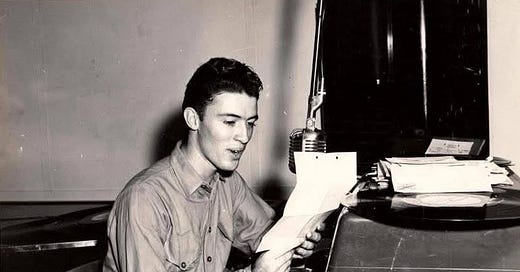

A photograph of Muni from this time and in this milieu captured a raw-boned, serious young man in a pensive, apparently late-night mood. A hint of perspiration suggests his tropic location.

He sits in a hard-backed wooden chair- the kind of heavy, utilitarian furniture that grows more uncomfortable the longer one occupies it — in a uniform to which someone, no doubt Muni himself, has taken a black marker and written his name, "Munoz, D.A.," serial number, "USMC," and, in letters much bigger than the rest, "New Orleans."

Before him is a concave table upon which rests the studio console. At two-and-half to three-feet wide, it looks like and probably was something out of the second world war, a metallic-faced machine fronted by a few spare switches and dials. Muni kept what copy he had to read on a makeshift document-holder that he placed atop the console, to the right-hand side of the mic.

A silver stand rises from behind the console and extends in toward the disc jockey, placing the microphone squarely in front of his face. A vinyl record spins on a turntable to Muni's right. Next to it is an empty paper record sleeve and the half dozen or so letters that arrived in the day's mail.

To Muni's left is another microphone, an ashtray, and the clipboard upon which he keeps the rudimentary program log. A black rotary telephone sits nearby. A cigarette case and two pens are within easy reach.

This was a sizable portion of Muni's world in the fall of 1949. While he could carouse as well as, if not better than, most of the GIs on the Island, he understood the tedium and fear and loneliness and dislocation behind the bar-clearing brawls and reckless behavior with local women.

Even now, not even out of his teens, empathy is a significant aspect of his personality. From the vantage point of WVTG, and the feedback he received both on and off the air, Muni saw how a record he picked — often at random, but sometimes in response to a request — could mean all the difference in the world to somebody listening “out there” in the dark.

The art behind the whole thing, Muni came to believe, was to have a “feel” for the audience and to deftly respond from the gut.

He might not always read the prevailing mood correctly, but more often than not he managed to play the right song at the right time for somebody, and his star began to rise.

Then he hit upon the idea of reading “Dear John” letters on the air.

As Muni explained to Ken Terry of Variety, the formula for his show was simplicity itself. Guys would send him their "Dear John" letters, he would read them, and then play songs that reflected the content or the mood the reading of the letter created.

“It was real easy,” he said.11

It also became an instant hit.

The challenge was having both enough new records to allow for a modicum of creativity in summing up the letters, and keep things interesting for both his listeners and himself.

That’s why, shortly after arriving home on leave in early December 1949, Muni determinedly made his way to Cosimo Matassa's shop, and how he happened into the recording session that would shape the rest of his life.

Although he had no way of recognizing it, the timing of his visit to the corkboard and tile-lined studio with its conical light sconces and primitive recording equipment, could not have been more auspicious.

The early salvos of musical and social revolution were underway, and because of them, radio in the mid- to late-1950s would be ripe for a new generation of talent and ideas.

Muni was back in Guam in January 1950, but by the spring, he was once again on the move, bouncing between Pearl Harbor and the U.S. west coast, and finally, in October 1951, winding up at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Photographs taken at these various outposts find Muni still rail thin, but growing in confidence and demeanor as he rose to the rank of sergeant. Most of the black and white shots were taken while Muni did “remotes,” the most unusual perhaps being a broadcast from the bedside of a soldier in traction in a Red Cross medical facility.

In one, Muni even wears a mischievous smile as he adjusts the dials on a “portable” studio set-up consisting of a turntable, a suitcase-sized control board and large RCA microphone.

Muni was discharged from Camp Lejeune in July 1952. What he found when he got out was a changed media landscape.

Where Bernice Judis and WNEW-AM progressed down one evolutionary path in the 1930s and 1940s, a new wave of entrepreneurs was experimenting with formats on the frontier of radio that would take the medium in unforeseen directions.

The advent of television, which blossomed as an industry while Muni was in the service, forced hundreds of stations to innovate in some fashion or die.

Critical to the future of progressive rock radio was the development of the Top 40 format, which ironically served both as the training ground for many of the first disc jockeys to populate the FM dial, and as the constrictive programming design they'd eventually rebel against.

There are many stories about how the Top 40 format was developed; the most reliable distillation comes from Fornatale and Mills in “Radio in the Television Age.”

In their telling, Top 40 was born after radio magnate Robert Todd Storz and his assistant Bill Stewart at KOWH in Omaha, Nebraska decided to walk to the bar across the street from the station for a drink.

Up to this point, both Storz and Stewart, like many independent radio men across the country, were students of WNEW’s success story and tried to adapt what Judis was doing in New York to their own situation. Mainly, that meant adopting WNEW's approach to block programming, an easy to follow formula of broadcasting carefully selected recordings in solid across-the-board segments.

But as they sat and talked on this particular night, they were struck by the fact the same songs were repeatedly being played on the jukebox.

“Near closing time, a waitress walked over to the jukebox, took change from her pocket, and played the same song three times in a row,” Fornatale and Mills wrote.12

The night turned out to be a revelation for the two men. Though KOWH sought to cater to its listeners’ tastes, they’d never realized how often people were willing to hear the same song if it appealed to them. Their fellow patrons at the bar convinced Storz and Stewart familiarity with the music was key to getting listeners to continue to tune in. Returning to the station the next day, they began to hash out a new approach to programming the station.

As they brainstormed, the broad outlines of a format were born. They would reduce the number of records played on the station and repeat listener favorites more often. At the same time the station itself would designate a “pick of the week” — typically the current number one hit across the country according to Billboard magazine — which would be played once an hour.

The Top 40 format was further refined during the 1950s by Texas pioneer Gordon McLendon, founder of the Liberty Radio Network, who introduced the idea that disc jockeys should be distinct, high-profile personalities in their own right, and that the new Top 40 music shows should also incorporate brief newscasts.

Thanks to his elevation of the disc jockey to celebrity, McLendon's KLIF in Dallas quickly became the city's top-rated station. To further pump up its ratings, McLendon spent thousands on contests and promotions to continually stoke audience interest.

A true industry maverick — think Ted Turner circa the 1970s and 1980s — McLendon, who died in 1986, would also be credited with creating the “beautiful music” format for KABL/San Francisco in 1959, and with starting the first “all-news” radio station at WNUS/Chicago.

Bringing the Ted Turner comparison full circle, one of WNUS’ reporters just happened to be future CNN anchor Bernard Shaw.

But it is with launching Top 40 that both McLendon and Storz will always be associated. Within a decade, and with the not inconsiderable help of The Beatles and the 1960s pop and rock explosion, the format would take New York by storm.

In the meantime, big changes were afoot on the music front. If radio was evolving toward a new form and new core audience in the mid-1950s, so too was the music that it was transmitting to an eager public.

© 2013

(Photo of a young Scott Muni courtesy of Zachary Taylor Martin)

Neer, Richard. FM The Rise and Fall of Rock Radio. Villard Books, New York 2001. Pages 48-49

Spitzer, Nick. The Story Of Fats Domino's 'Ain't That A Shame' National Public Radio. May 1, 2000

1920 U.S. Census

"Operating Statistics". Department of Aviation, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport. March 23, 2011.

Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel

Brinkley, Douglas The Man Who Won The War For Us, American Heritage, 20000101, Vol. 51, Issue 3

Terry, Ken. "Muni Tends Flame of Progressive Rock." Variety. October 28, 1987.

Terry, Ken. "Muni Tends Flame of Progressive Rock." Variety. October 28, 1987.

Scott Muni interviewed by Pete Fornatale for a Pratt University class. Date unknown.

Terry, Ken. "Muni Tends Flame of Progressive Rock." Variety. October 28, 1987.

Terry, Ken. "Muni Tends Flame of Progressive Rock." Variety. October 28, 1987.

Radio in the Television Age, by Pete Fornatale and Joshua E, Mills, The Overlook Press, Woodstock, N.Y. 1980. Page 27.